Tags

Alphonse de Lamartine, Cave art, Charles de Gaulle, Diane Arbus, E.M. Halliday, J.H. Plumb, Joseph Barry, Karl Marx, Kenneth Lamott, Lascaux, Leisure, Marin County, May 68, Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, Revolutions of 1848, Roy McMullen, Thomas Rowlandson, Tony Ray-Jones, W.P. Frith, William Hogarth

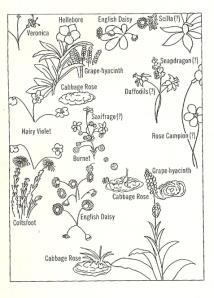

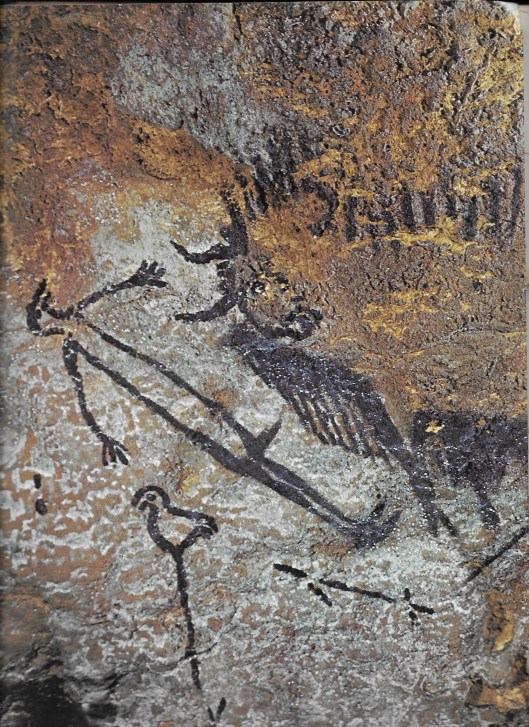

This issue’s cover illustrates Roy McMullen’s ‘The Lascaux Puzzle’ describing the cave art discovered in France in 1940:

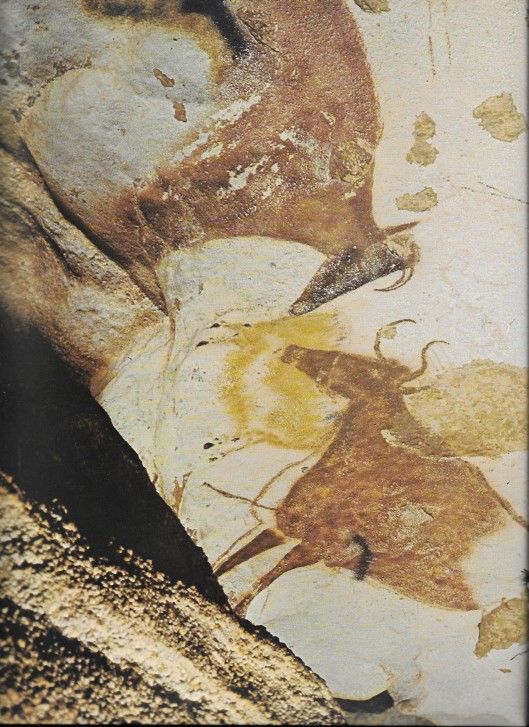

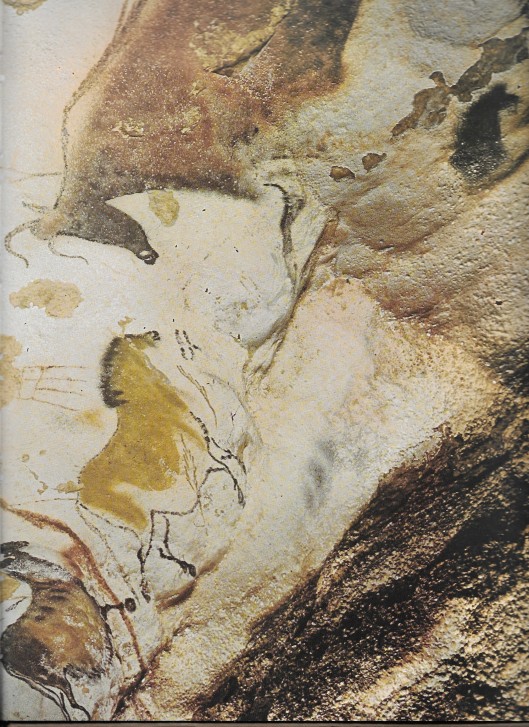

…[To] refer to Lascaux as the birthplace of art is to trade a high mystery for a cheap piece of romanticism. Art is forever being born, and its birthplace is the nature of Homo sapiens. We ought to avoid being condescending in our judgment of the achievement of the typical Lascaux artist. One way of being condescending is to be excessively tender toward him: to ignore, for example, the plain truth that his crudely scribbled ‘dead man,’ whatever interest it may have for anthropologists, is poor stuff by any artistic criterion. And another, more subtle way of being condescending is to speculate on his supposedly nonpainterly reason for painting.

…Who, back in 15,000 BC, constituted the public for the Lascaux paintings?

…[The] conclusion seems inescapable. Execution was all, looking was nothing. There was practically no public at Lascaux (nor at other decorated caves, for the evidence is about the same everywhere).

This conclusion can be neatly fitted into the assumption that the typical Lascaux artist was not so much an artist as a priest or maker of hunting magic…But all this does not get us out of the difficulty of believing that such expert and loving rendering of the visible world was simply a very private sort of action art, like bathroom singing. Can a situation so repugnant to our sentiments and our common sense, and so unparalleled in the history of naturalistic art, have really existed? Have I missed a clue somewhere?

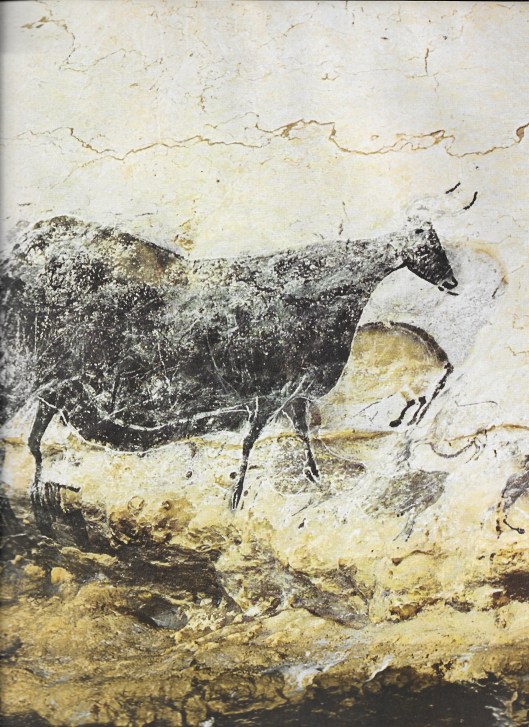

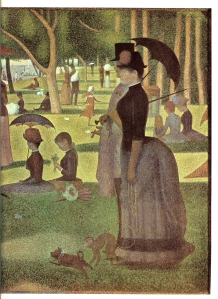

Horizon caption: ‘…in a gallery off the main hall, a frescolike ceiling decorated with cattle and horses, the latter somewhat reminiscent of those in Chinese art[.]’.

Also in this issue:

The issue contains a special section on the subject of ‘Leisure’ – with Horizon’s trademark approach of seeing the issues of the present in the light of the past.

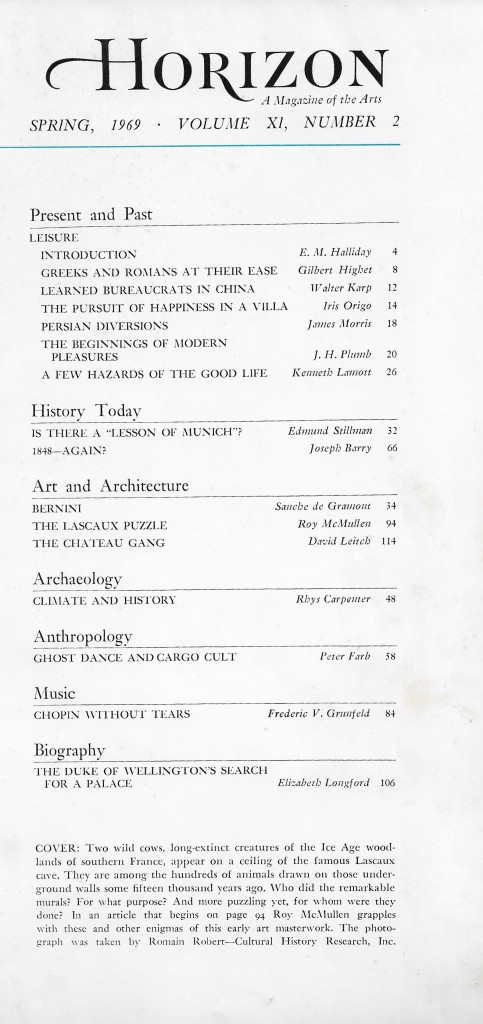

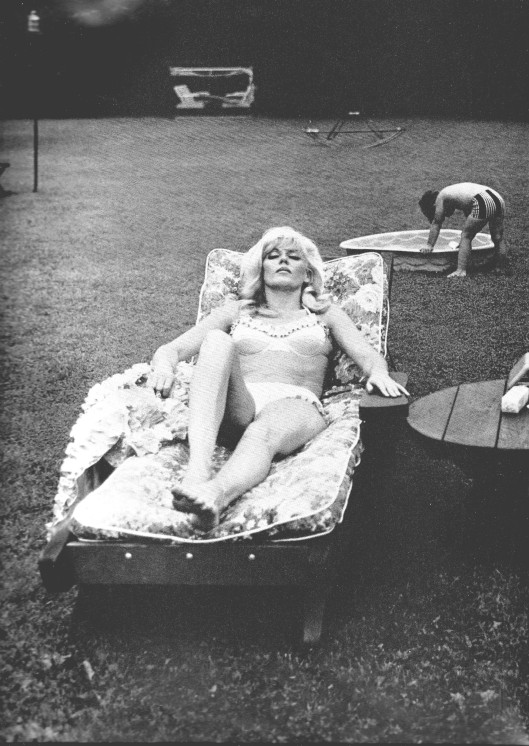

The section begins with a cropped version of Diane Arbus’ 1968 photograph ‘A Family On Their Lawn One Sunday in Westchester, New York’:

In an introduction, E.M. Halliday writes:

The essays that follow are by way of taking an eclectic view of what leisure has meant in various cultural environments throughout history – ending with a hard look at American leisure in Marin County, California, a place that seems to epitomize almost too well the current American ideal of the good life.

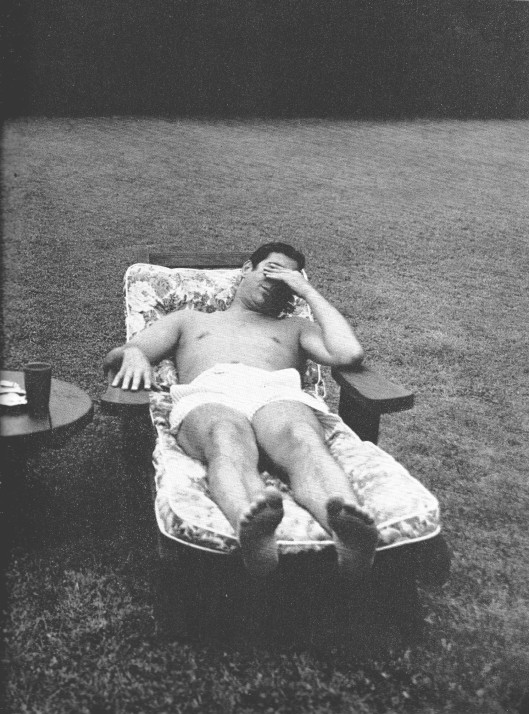

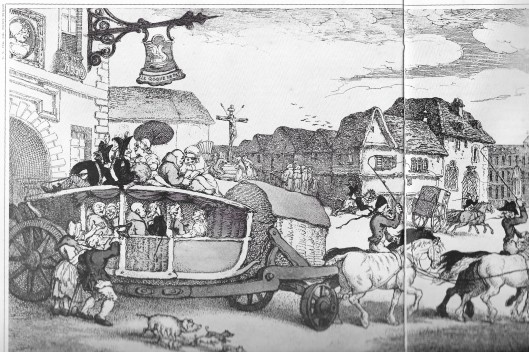

In ‘The Beginnings of Modern Pleasures, frequent Horizon contributor J.H. Plumb explores how in eighteenth-century England ‘the games of kings became accessible to all’, with horse racing, prize fighting and cricket all becoming popular in the 18th century:

Soccer, the game of the peasants and workers, did not become organized and a public spectacle until the nineteenth century, when the working classes first obtained a little leisure. The process was twofold: eager public participation turned amateur sporting activities into highly professional organized games involving stadiums, capital, and traditions of all kinds. The road to Santa Anita, Madison Square Garden, and the Houston Astrodome had been started.

The same popularisation was happening in culture, where in the mid-17th century:

Culture was personal or the affair of a narrow, rich, and generally aristocratic social class…Genteel places of amusement scarcely existed.

A hundred years later all was changed, and again England, with its ever-increasing prosperous middle class, led the way. Concerts were now a commonplace, as well as opera and ballet. The Royal Academy, founded in 1768, provided a yearly feast of art, but, better still for the growing culture-minded public, artists secured a copyright for engravings of their pictures by an act of Parliament passed in 1735 [sic]. William Hogarth leaped in at once, and soon handsome etchings of his masterpieces – Marriage á la Mode, A Rake’s Progress, etc. – were festooning the walls of middle class houses, along with the famous beauties of Joshua Reynolds or Thomas Gainsborough. The British Museum came into being in 1753, the very first of the great metropolitan museums

…Leisure had come to stay; man was at last on his way to turning his world into a playground.

In ‘A Few Hazards of the Good Life,’ Kenneth Lamott writes about the dissatisfactions of living in the seemingly-idyllic Marin County, one of the most affluent counties in California. He begins with a conversation with a man who ran an institute for treating alcoholics who told him that ‘a survey had shown that the hardest-drinking people around San Francisco were the American Indians in the Oakland slums and the residents of the Tiburon peninsula in Marin County’ on which Lamott had lived for seventeen years by 1969:

Having three children myself, I have given a good deal of thought to the lives they lead and have arrived at the considered judgement that Marin is a lousy place for kids to grow up in. Like the Negroes [who made up 2% of the population in Marin in 1969], they stand outside the Good Life, which is largely a white adult notion. For the kids, it’s great to be able to camp out on the slopes of Mount Tam or dig in Indian burial mounds or play tennis after school seven days out of ten the year round or sail an El Toro out of the back yard, but the real thing that’s on their minds is What’s it all about, man?, and the style of life we’ve evolved here doesn’t give them a very convincing answer…

The pathetic and dreadful secret is out: Nothing really matters very much. Winning a yacht race is just as important as winning a case in court. Playing a first-rate game of tennis is just as important as painting good pictures. Remodeling a house with one’s own hands is just as important as taking a class of freshmen through Heart of Darkness. Nothing really matters very much, but the view of the bay is great.

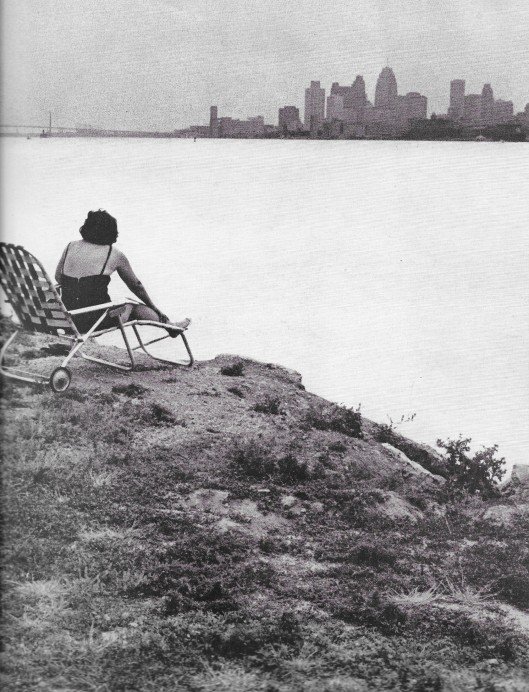

The section ends with Tony Ray-Jones’ 1965 photograph: ‘Belle Isle Park, Detroit’.

Horizon caption: ‘Sunday afternoon, Detroit’

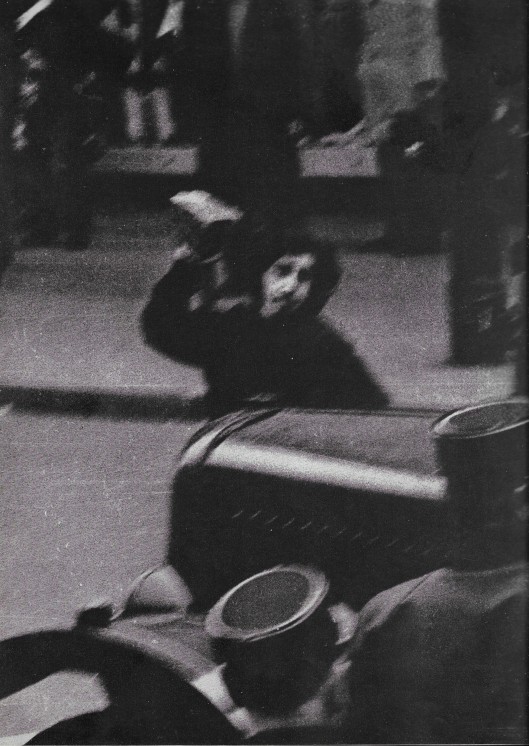

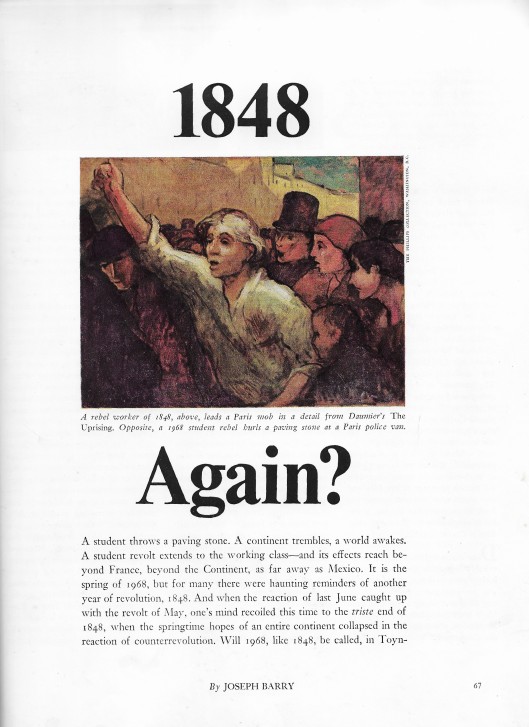

In ‘1848 – Again?’ Joseph Barry writes about the wave of revolutions which swept across Europe in that year, which seemed to be echoed by the events of May 1968 in Paris, where he was living at the time. He asks whether 1968 would, ‘like 1848, be called in Toynbee’s phrase, a turning point where history failed to turn? Or, as the Germans viewed the earlier revolt, that “crazy and holy year”?’:

Does reaction follow revolt as inevitably as one tide the other? Or was it simply the swiftness of reaction that was so extraordinary in 1848? In any case, everything about that year has a breathless quality. The Age of Metternich, which had extended from the Congress of Vienna in 1815 ad infinitum, it seemed, came to a sudden end in February 1848; and within the next six weeks a dozen conservative rulers fell like so much ripe, if not rotten, fruit…

‘France is bored,’ the political correspondent of Le Monde wrote less than two months before the student revolt in May, 1968. He was quoting, with an uncanny parallel, a statement of the poet-politician Alphonse de Lamartine on the eve of the 1848 revolt.

But there was more than boredom that soon shook the French regime of 1848. The revolution of 1789, Lamartine had also pointed out, had simply replaced the ‘domination of a king by that of wealth…instead of one tyrant, there were now several thousand.’ It was the propertied who constituted le pays legal, the legal country: less than 250,000 were privileged to vote in a land of thirty-five million.

Barry concludes:

[L]ibertarian movements…were to await, like nationalism, a riper moment. In France there was also the prophetic element of a purely proletarian movement. Marx explained its failures: ‘The bourgeois republic triumphed. On its side stood the aristocracy of finance, the industrial bourgeoisie, the middle class, the petty bourgeois, the army, the lumpenproletariat organized as the Mobile Guard, the intellectual lights, the clergy and the rural population. On the side of the Paris proletariat stood none but itself.’

In any handbook on How to Steal a Revolution, the first principle, based on the 1848 experience, might well be: insist on immediate, democratic elections. It was a lesson de Gaulle heeded last June when he called for a swift vote to end the risings of 1968. Civil strife, the sound of violence, the great uncertainties, bring cries for the maintenance of order – that is, generally, the old, familiar order. And there is nothing so frightening for a majority as the first stages of a revolution.

On the walls of the student-occupied Sorbonne last May was scrawled: ‘Universal suffrage is counterrevolution – Proudhon.’ Lenin and Castro were not to make that mistake.