Tags

Antonine emperors, Board of Trade, Canton, China, Christoper Hibbert, Commodus, Edmund Burke, Edward Gibbon, Georges Deyverdun, Ghiradelli Square, Harold L. Bond, Howqua, Lausanne, Lawrence Halprin, Lord Napier, Marcus Aurelius, The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, Thirteen Factories

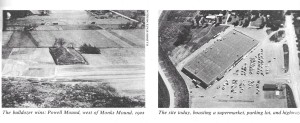

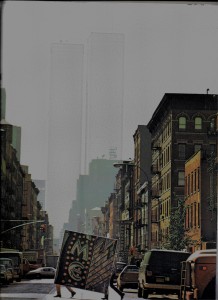

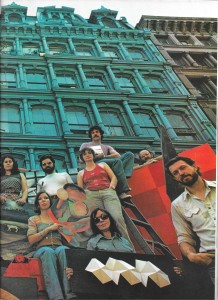

In ‘Lawrence Halprin: Eco-architect’ David Lloyd Jones explores the work of the American landscape architect and pioneer of adaptive re-use of buildings, such as San Francisco’s Ghiradelli Square:

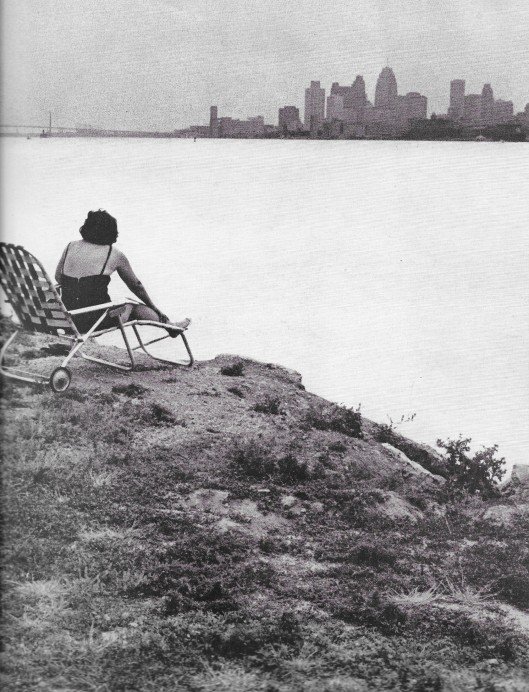

Halprin says his best work is done for daring clients, men who are willing to risk their money on good ideas and have the guts to live the risk through. One of these is William Roth, who bought the old Ghirardelli chocolate factory buildings on San Francisco’s waterfront to save them from destruction. An enchanting tangle of box factory, clock tower, manufacturing bays, and storage space, it was not clear that the old buildings were anything but a monument to nineteenth-century achitectural whimsy. With architects Wursterm Bernardi & Emmons, Halprin’s firm turned the block into an intriguing and commercially successful array of boutiques and restaurants.

To say Halprin is proud of the crowds of people moving, exploring, and enjoying themselves around the square would be an understatement. The purpose of his art, the principle for which he strains, is designing for people – real, moving people, not the people of abstract designers’ principles. The triumph of architecture is not, as the International stylists would have us think, in looks, lines or majesty. Forty years of these criteria have left us only blank-faced monuments and city blight. Successful architecture is usable and used.

Ghirardelli Square, the old factory site, attracts people because it is interesting and humane; it is architecture real people can relate to Young couples come here just to walk around, without paying the fairly steep prices charged by most of the establishments. Elderly ladies sit and watch the seaport over a cup of espresso because the place is that kind of pleasant spot to be in. People go out their way to shop in the square’s boutiques because the friendly, cheerful bustle makes shopping such fun.

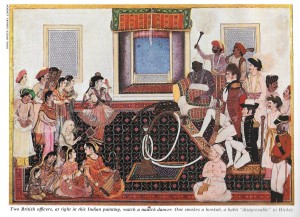

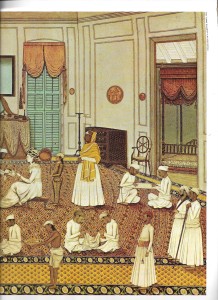

In ‘Tremble! Intensely Tremble!’ Christoper Hibbert describes the British trade envoy Lord Napier’s abortive 1834 expedition to Canton, in an extract from his book The Dragon Wakes: China and the West, 1793-1911:

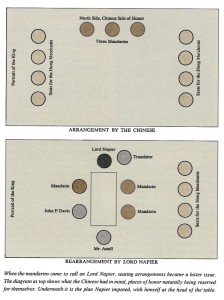

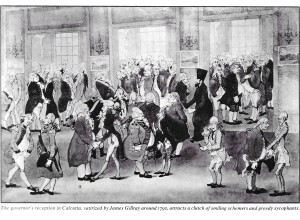

Two hours before they were due, a party of Chinese arrived at the factory [in Canton], where the interview was to take place, carrying a number of ceremonial chairs. Three of the chairs were arranged in a row facing south, the direction in which Chinese authority was traditionally required to face; the other chairs were placed in two rows at right angles to the first, running along the western and eastern sides of the hall. One of these rows had its back to the portrait of George IV. The three great mandarins, the Chinese said, would naturally take the seats facing south, the Hong merchants, the others; no seats were provided for the English.

Lord Napier was outraged when told of these impertinent arrangements and gave immediate orders for the position of all the chairs to be changed so that none would have its back to the king’s picture. He himself would sit in the place of honour, he decided, with one mandarin on his right and two on his left; his secretary, Mr. Astell, and the assistant superintendent, John Francis Davis, would occupy the remaining two seats at the table.

When Howqua arrived at the factory, he was appalled by the way the English had altered the position of the chairs. He begged Lord Napier not to insist upon a disposition that could only cause grievous offence to the dignity of the mandarins and that could only result in the punishment of himself and the other Hong merchants, who would be forced to pay crippling fines. Such an arrangement of the seating would, no doubt, be very proper in England, but this was China. Could not Lord Napier give way in this small point for the sake of the Hong merchants, who relations with the foreigners had always been so friendly, and if not for them, at least for the happy continuance of trade?

No, Lord Napier decidedly could not…

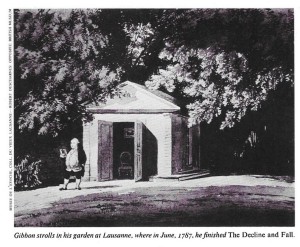

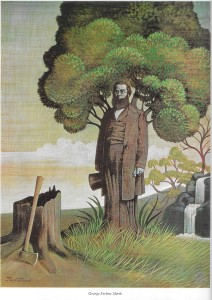

In the title of ‘Gibbon: “An ugly, affected disgusting fellow”‘, Peter Quennell uses a quote from James Boswell to describe the author of The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire:

At length, in February, 1776, the first volume of The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire was delivered to the London bookshops, whence it soon found its way into every library, onto ‘every table’ and ‘almost every toilette.’ Before long it had run through three editions. Volumes II and III appeared in 1781. They were not the product of a cloistered scholar. During his London residence Gibbon contrived to lead a remarkably energetic social life; he sat in Parliament as member from a Cornish borough – he enjoyed listening to a hard-fought debate, but, no doubt wisely, never spoke himself – and held a comfortable sinecure at the placid Board of Trade. It was Edmund Burke’s thundering attack on sinecures, followed by the reform of the board and the abolition of his own post, that finally determined him to leave England. In September, 1783, with his valet and his lap dog, Muff, he bade good-bye to London and crossed the Strait of Dover, bound for Lausanne, where an old friend, Georges Deyverdun, had invited him to share his house. Four years later in the garden of that house he brought his grand design to a triumphant close.

The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire is one of the most astonishing books ever published in the English language – unusually long, yet extraordinarily easy to read; a work of tremendous scholarship, yet imbued throughout with the characteristic quality of a single man’s intelligence. The historian’s tone is cool and calm, and measured, but strong feelings, even violent prejudices, often boil beneath the surface. Gibbon was an eighteenth-century humanist, anxious to demonstrate (writes Professor Harold L. Bond in an admirable study, The Literary Art of Edward Gibbon) ‘that the dignity and nobility of the human spirit are possible only under conditions of political and spiritual freedom.’ Thus he begins with an eloquent tribute to the Antonine emperors and to the civilization they had built around them, comprehending ‘the fairest part of the earth and the most civilized portion of mankind,’ protected by ‘ancient renown and disciplined valour,’ and unified by the ‘gentle but powerful influence of law and manners.’

This was a world where men like the historian could have lived contentedly and profitably and dwelt at peace among their fellows. Gibbon’s purpose is to show, after the death of the enlightened emperor Marcus Aurelius and the succession of his brutal successor, Commodus, the Roman world had become uninhabitable for human beings of his own kind.