Tags

A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte, American Civil War, Charles II, Correlli Barnett, Georges Seurat, Karl Maria von Clausewitz, Nell Gwyn, On War, Pointillism, Roy McMullen, Samuel Pepys, Vietnam War

Part 2 of this issue:

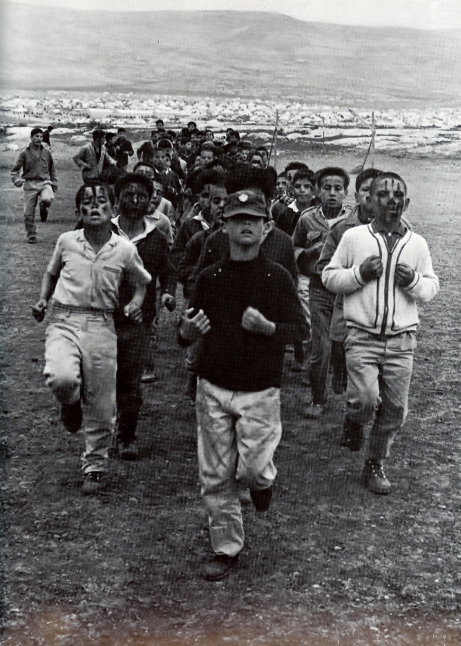

In ‘How Not to Win a War’ the eminent British historian Correlli Barnett writes about the book that was a key influence on him, and which he says could help explain what he calls ‘the American defeat in Vietnam‘, though the end of the war was still four years away:

General Karl Maria von Clausewitz was the first man to make conceptual sense of war as a social and political activity and to deduce its governing principles. Clausewitz is the starting point of all later theorizing about war, and often the finishing point as well. He significantly influenced the German and French general staffs before 1914; he is the fountainhead of present-day Communist thinking about war; and he ought to be a part of every Western young man’s education. His great work On War (Vom Kriege), casts more light than any other single book on all the facets of collective human rivalry…

…Clausewitz’s philosophy of war has been garbled into dogma, with regrettable results.

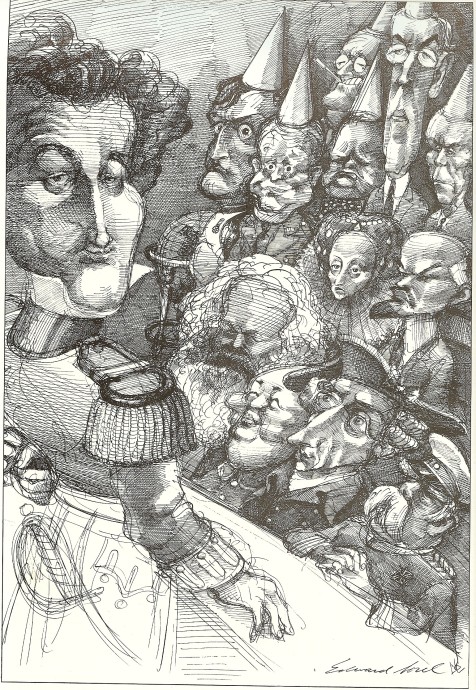

Horizon caption: ‘Who would have won the honors if Clausewitz had taught a seminar on war? In Edward Sorel’s reunion portrait, the bright students sit up front below their master.’ Front row, L-R: Marx, Mao, Frederick the Great, Bismarck. Second row, L-R: Elizabeth I, Lenin. ‘Dunces’ in the rear, L-R: Napoleon, Eisenhower, F.D. Roosevelt, Churchill, Wilson, Marshall.

War for Clausewitz was no meaningless episode of violence, nor was it absolutely distinct and separate from peace. War, on the contrary,

‘belongs…to the province of social life. It is a conflict of great interests which is settled by bloodshed, and only in that is it different from others. It would be better…to liken it to business competition, which is also a conflict of human interests and activities; and it is still more like State policy, which again…may be looked upon as a kind of business competition on a grand scale.’

This simple proposition is Clausewitz’s greatest and most illuminating insight. In the words of his most quoted aphorism, “War is only a continuation of policy by other means.” Clausewitz returns again and again to this theme of the continuity of international relations, from peace via war to peace again, speaking of a diplomacy that (in war) employs battles instead of notes. It follows that the conduct of war ought to be constantly governed by political considerations.

In Clausewitz’s view, it is absurd to try to “win” wars by military means alone, because, as he says, no major plan of war can be made without political understanding and insight. The political setting not only determines the aims and decisions of war strategy but also colors the whole character of the war…

It was not the nature of nineteenth-century warfare that made the American Civil War so long and bloody but the irreconcilable political and social issues of secession and union, slavery and emancipation. And it is political, not military, considerations that have prevented the United States from using nuclear weapons in Vietnam – on the contrary, nothing would so economically and efficiently block the Vietcong supply routes.

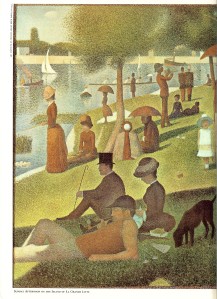

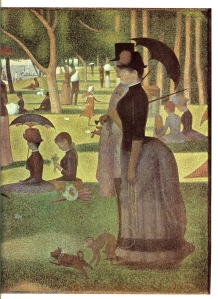

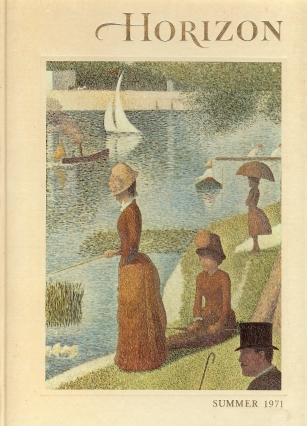

In his study of Seurat’s A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte, Roy McMullen explores the hostile response to it:

Nervousness and defensiveness are, of course, unprovable, but they become at least a faint, mischievous possibility when we remember that viewers in 1886 were still uncowed by avant-garde art and were without our modern emphasis on the formal and abstract elements in painting, and were therefore more sensitive than we are likely to be to the figurative message – the moral, to use a nineteenth-century term – of La Grande Jatte.

For there actually is such a message, or moral, in the picture, however much it is ignored by art historians intent on optical effects and spatial organization or by ordinary appreciators engrossed in summertime and bustles. And a similar message can be detected nearly everywhere in Seurat’s mature achievement, rising like a slightly corrosive odor from his characteristic mixture of loveliness, banality, delicacy, and pedantry.

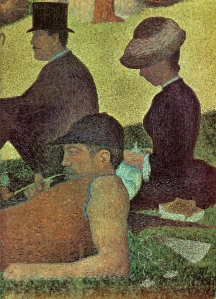

A whiff could have made a boulevardier at the Maison Dorée feel obscurely menaced. Consider, as an example, the pipe-smoking boater and his two elegant neighbors in the left foreground of La Grande Jatte…At first glance these impressively monumental figures – naked, the boater could be an antique river deity – seem drenched in the sedative bliss of a sunlit holiday; at second glance the bliss drains away. One of today’s veristic film directors could scarcely ask for more eloquent images of urban man’s loneliness in a crowd and his inability to communicate with his fellow men.

The same solitude seems to shroud, with a few doubtful exceptions, everyone in the picture, including the mysteriously motivated hornblower in the tropical helmet and even the “superb cocotte” despite her decorative pet and her evidently affluent protector.

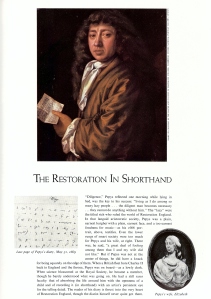

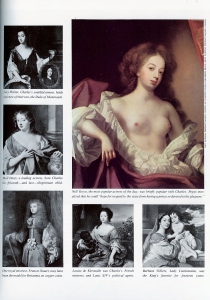

‘The World of Samuel Pepys’ is a lavishly illustrated look at the life of the Restoration diarist:

Also included with this issue is a supplement: an eight-page panorama of London in 1647.